The Balance of Passions |

|

Hippocrates,

Hippokratous . . . Iatrike, This is a Renaissance edition of works by Hippocrates, with parallel text in Greek and Latin. |

|

This story begins as did so many other components of our culture, in Greek and Roman antiquity where medicine first emerged as a secular activity independent of religion. There Hippocrates (ca. 460 B.C.Bca. 370 B.C.) and his followers combined naturalistic craft knowledge with ancient science and philosophy to produce the first systematic explanations of the behavior of the human body in health and illness. Distant ancestors of modern biomedical scientists began to explore the solid and fluid parts of the human organism for keys to unlock the hidden mechanisms of disease. They made the first attempts to understand emotions as mental phenomena which had surprising and complex connections to physiological order and pathological disorder. Early Western physicians recognized that emotions were of essential significance; however their medical systems were actually weighted more heavily on the body side of the mind-body balance. The dominant theory of Hippocrates and his successors was that of the four "humors": black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. When these humors were in balance, health prevailed; when they were out of balance or vitiated in some way, disease took over. The goal of an individual's personal hygiene was to keep the humors in balance, and the goal of medical therapy was to restore humoral equilibrium by adjusting diet, exercise, and the management of the body's evacuations (e.g.: the blood, urine, feces, perspiration, etc.). 1 The bedside scene from Walter Ryff's Spiegel und Regiment and the diagram from Johannes de Ketham's Fasciculus Medicinae, although both from later periods, clearly illustrate these classical themes. |

|

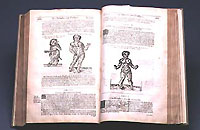

Johannes

de Ketham Johannes de Ketham, a professor of medicine in Vienna, published Fasciculus Medicinae, which included illustrations on bloodletting and urine flasks showing the "resemblance of the elements and the bodily constitutions." This an English translation of Latin text. |

|

|

|

Emphasizing the humors gave classical medicine what modern philosophers call a "reductionist" bias--the humors were used to explain more complex phenomena like emotional states in much simpler physical terms. For example, when a patient was melancholy, physicians assumed that his or her complicated feelings of sadness and depression resulted from the physical excess of black bile. Likewise, an excess of yellow bile was thought to make a person angry and impulsive. In the Hippocratic treatise The Sacred Disease, the author explains that "those maddened through bile are noisy, evil-doers and restless, always doing something inopportune" 2 ; this explanation assumes that emotions are the more complicated consequences of the simpler and prior humoral causes. Even in the unmistakably reductionist Hippocratic writings, however, certain emotional states appear as causal elements. In one case, a woman began to exhibit fears, depression, incoherent rambling speech, and the uttering of obscenities after suffering from a "grief with a reason for it"; and another "without speaking a word . . . would fumble, pluck, scratch, pick hairs, weep and then laugh, but . . . not speak," also "after a grief." 3 In The Sacred Disease, epilepsy is said in certain circumstances to be "caused by fear of the mysterious." 4 Emotional factors played only a minor role in the subsequent development of classical medical thought because authors after Hippocrates continued to rely primarily on humoral-reductionism and did not actively pursue emotional causal elements. These medical authorities worked hard to clarify and codify the humoral ideas embedded in Hippocrates's work. They also systematized a therapy based on "opposition," whereby excess humors were depleted and "cold" medicines such as oil of roses countered "hot" diseases like fevers and vice versa. Some writers in late antiquity also added important anatomical features to their reductionist medical systems. 5 |

|

Justus

Cortnumm

|

For much of the medieval and Renaissance periods, Galen and Hippocrates were regarded as co-equal medical authorities, with Galen even assuming a superior position for certain medical teachers or commentators. In the seventeenth century, however, the more empirically oriented Hippocrates came to be regarded as superior to the more theoretical Galen. This distinction between the two men is depicted here on the title page by Hippocrates touching the rosebush on the side of the flowers and Galen touching the side of the thorns. |

|

But another dimension to medical thought became increasingly prominent in later antiquity. This was the orientation towards emotions as causes strongly influenced by Galen (A.D. 131-201). Known for his prolific writings and his essential loyalty to humoralism, he was accepted in the medieval and renaissance periods as coequal with or even superior to Hippocrates. Deeply respected for his diagnostic skill, Galen was celebrated for his differential diagnoses, especially for those which distinguished between illnesses traceable to orgnaic causes and those which seemed to mimic them but were actually traceable to emotional causes instead. In one famouse case he treated a young woman who seemed to exhibit the signs of physical illness but who, upon closer examination, revealed no organic pathology. After eliminating any possible humoral explanation, Galen identified the real, emotional cause of her somatic symptoms: a hidden love interest. 6 He used the sudden irregularity of her pulse as a crucial diagnostic clue. |

| Galen is making a diagnosis of love-sickness. | |

|

Galen, |

|

... I came to the conclusion that she was suffering from a melancholy dependent on black bile, or else trouble about something she was unwilling to confess. Galen

|

|

Galen likewise contributed an important new interest in the balance not only of the humors but of what he called the "non-naturals," among which he included the "passions or perturbations of the soul." 7 According to the doctrine of the non-naturals--which was incorporated in medieval medical books alongside the humors--it was important for physicians to help patients keep their emotions in balance, for the sake of their bodies as well as their mental states. The influence of strong emotions on physical health and illness thus became a central tenet of medical belief which grew progressively stronger in the medieval period. As rabbi, philosopher and physician Moses Maimonides expressed the point in the twelfth century, "It is known . . . that passions of the psyche produce changes in the body that are great, evident and manifest to all. On this account . . . the movements of the psyche . . . should be kept in balance . . . and no other regimen should be given precedence." 8 |

|

Moses

Maimonides (1135-1204), |

|

|

Gregor

Reisch (d. 1525),  |

Gregor Reisch included an often-reproduced woodcut profile of the head in his book Margarita Philosophica. The figure locates various faculties of the soul (cogitation, memory, etc.) in specific regions. Note that Imaginativa (imagination) is located directly over the eyes. |

|

Ideas about the "balance of the passions" were popular in the Renaissance and early modern periods. One famous work showing how influential these ideas would become is Robert Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy which included the following observations about the possibly disastrous role of unchecked emotions: "the mind most effectually works upon the body, producing by his passions and perturbations miraculous alterations . . . cruel diseases and sometimes death itself." 9 Also in this period, speculation about the role of the "imagination" added other elements to the non-physical causes of disease. Some authors suggested that the imagination affected the body directly by its immaterial agency, others that it operated indirectly by first arousing the emotions which, in turn, "are greatly alterative with respect to the body." 10 There was general agreement that emotionally-charged ideas could exert enormous effects, as in the case of the monstrous "frog baby" produced by vivid maternal imagination, reported by Parť. |

|

The physician should make every effort that all the sick, and all the healthy, should be most cheerful of soul at all times, and that they should be relieved of the passions of the psyche that cause anxiety. Moses Maimonides (1135-1204)

|

|

Speculation about the influence of the "imagination" was intense during the Renaissance period. It was widely believed that vivid ideas could lead to various bodily consequences, including diseases and monstrous births. Parť, a famous early surgeon, reported on two cases, one of a child born with the body of a calf, and another that occurred in 1517, of a child "born having the face of a frog," produced by the power of the mother's imagination. The mother, advised by her neighbor to hold a live frog in her hand as a means to cure her fever, was still holding the frog that evening, when she and her husband conceived a child. |

Ambroise

Parť (1510?-1590),  |

|

William

Falconer (1744-1824) |

|

Intellectuals and lay people alike were strongly committed to these ideas in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. While certain philosophical fashions within the medical community changed to reflect the Scientific Revolution going on around it, much medical practice remained traditional and fundamentally unaltered. Consideration of the role of the imagination and of strong emotions in the onset and course of illnesses continued into the nineteenth century. Medical literature included extensive essays and specialized monographs on emotional states and their impact on somatic health and disease. 11 One example is William Falconer's A Dissertation on the Influence of the Passions Upon the Disorders of the Body. |

|

Honorť

Daumier (1808-1879) The husband is attempting to lead his pregnant wife away from the cage of the great apes at the zoo. He is afraid that by looking at the ape in her condition, she might give birth to a deformed baby. The longstanding belief that the vividly stimulated imagination of pregnant women could lead to "monstrous" births persisted in popular culture well into the nineteenth century. |

|

|

In many ways, however, the close of the eighteenth century marked a new era. As part of the Scientific Revolution, anatomical investigation once undertaken in antiquity had revived and became a hotly pursued field of study. Andreas Vesalius in sixteenth century Padua and Thomas Willis in seventeenth century Oxford were just two of the many bold explorers who cut into the body, probed its structure, and displayed their findings in beautifully illustrated works. In the eighteenth century, physicians increasingly turned to anatomy as a foundation for pathology. As a result, disease processes were progressively "localized," that is, said to reside primarily in the disruptions or "lesions" of the solid parts of the body rather than in the imbalance of humors. Post mortem dissection became an increasingly common medical practice. 12 |

|

Andreas Vesalius |

Andreas

Vesalius (1514-1564), |

What is particularly notable about this scene of Vesalius about to perform an autopsy is his gaze, directed away from the cadaver, and his hand resting on the left arm, almost as if taking a pulse. Like the Chartran portrayal of LaŽnnec, this nineteenth-century image strongly conveys the anatomical basis of the new medicine. |

|

|

Andreas

Vesalius's

Illustration of dissecting instruments from De Humani Corporis Fabrica. The De Fabrica, the first modern work of anatomy, was initially published in 1543. This plate is enlarged from the 1568 Venice edition. |

|

Thomas

Willis (1621-1675), An outstanding example of seventeenth-century anatomical achievement was Thomas Willis's Cerebri Anatome (On the Anatomy of the Brain), first published in 1664. Shown here are Willis's engravings of the human brain (left Page) and of the sheep brain (right page). |

|

|

At the turn of the nineteenth century, diagnostic breakthroughs swiftly succeeded the maturation of gross pathological anatomy. R. T. H. LaŽnnec invented a primitive stethoscope (he called it a "cylinder") to help him hear inside his patient's body and thus imagine what the parts "looked" like because of the particular sounds they elicited. In the process of concentrating their attention on the anatomical abnormalities of the solid parts of the body during an illness and as a result of disease, LaŽnnec and other physicians of his time gained precision in their diagnoses but began to lose the immediacy and intimacy of verbal contact with their patients. 13 Clearly captured in Chartran's painting of LaŽnnec performing a physical examination is the growing communication gap between doctor and patient, each seemingly contained in his own separate world. This stands in sharp contrast to the scene typically depicted at the medieval bedside. |

|

LaŽnnec-style

Stethoscope

In 1819, LaŽnnec first described his powerful new diagnostic invention, the cylinder-like stethoscope. The physician placed one end of the instrument on the patient's chest and his ear to the other, so he could listen to the sounds of disrupted anatomy within. |

|

LaŽnnec

,

|

Renť

Thťophile Hyacinthe LaŽnnec

De l'Auscultation Mťdiate, ou, Traitť du Diagnostic des Maladies des Poumons et du Coeur (On Mediate Auscultation, or, Treatise on the Diagnosis of the Diseases of the Lungs and Heart), Paris, 1819 The stethoscope is illustrated here in a fold-out plate with parts of the lung shown at the right. |

|

The further development of microscopic anatomy by Rudolf Virchow and others in the nineteenth century led to greater knowledge of tissues and cells. This development, unfortunately, also fragmented the notion of organismic unity implicit in classical and early modern medical theory. 14 Emotions became more and more separated from disease. |

Rudolf

Virchow , Rudolf

Virchow ,Die Cellularpathologie in ihrer BegrŁndung auf Physiologische und Pathologische Gewebelehre, Berlin, 1858 In Virchow's most influential book, Die Cellularpathologie, he described and depicted the precise microscopic structure of cells--including nerve cells--but seemed to leave no place in the body's operation for the influence of the emotions. |

|

|

By the mid-nineteenth century, however, a place was secured for emotions in connection with disease even as post mortem anatomy and cellular pathology advanced. Already in the eighteenth century William Cullen had noted that patients with certain major disorders--"insanity", for example--did not always show the expected organic lesions upon post mortem dissection. He reasoned that, instead, such patients may have developed "a considerable and unusual excess in the excitement of the brain" and that this excitement could in turn have derived from "violent emotions or passions of the mind." 15 Cullen and Robert Whytt were two of the many physicians who turned to the nervous system to find a physiological connection between emotions and disease. These physicians hoped to find in nervous system physiology a compromise of sorts between traditional ideas linking emotions and disease and the new desire to extend the reach of localistic pathology. Since the nervous system was enormously complex and its functions were subtle and elusive, it could be the locus of "functional" disorders, which were characterized by disrupted activity but where no inflammation or "appreciable morbid change in the nervous structure" could be found. By the 1840s and 1850s, functional disorders of the nervous system (also called "neuroses") and the emotional causes that precipitated them had become a major area of clinical study, as is clear in Austin Flint's popular A Treatise on the Principles and Practice of Medicine. |

|

William

Cullen (1710-1790), |

| ...in many instances of insane persons, their

brain had been examined after death, without showing that any

organic lesions had before subsisted in the brain, or finding that

any morbid state of the brain then appeared.

William Cullen

|

|

Austin

Flint (1812-1886), |

|