.

Mysterious Viruses as Bad as They Get

.

Mysterious Viruses as Bad as They Get

.

By Denise

Grady

The New York Times

Tuesday 26 April 2005

Uíge, Angola - Traditional healers here say their grandmothers knew of a bleeding disease similar to the current epidemic of hemorrhagic fever that has killed 244 of the 266 people who have contracted it. The grandmothers even had a treatment for the sickness, the healers told Dr. Boris I. Pavlin of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But the remedy has been lost. The old disease was called kifumbe, the word in the Kikongo language for murder.

|

No one can say for sure what kifumbe (pronounced key-FOOM-bay) was, and in some ways the Marburg virus is almost as mysterious. More than a month has passed since it was identified as the cause of the deadly outbreak here - the largest Marburg epidemic on record - but some of the most basic questions about the epidemic have yet to be answered. How and when did this rare virus get here? Why have so many victims been children? And how could so many have become infected before the disease was recognized?

The high death rate, over 90 percent, is also puzzling, but it is too soon to tell whether the rate is really that high. In past outbreaks, mortality has been lower. In Uíge, milder cases may be going unrecognized.

"It is easier to count the dead people," said Dr. Pierre Rollin, a physician in the special pathogens branch of the C.D.C. "The numbers in the beginning don't mean anything."

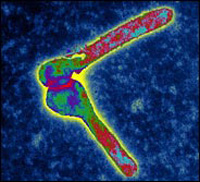

Viral hemorrhagic fevers, a handful of diseases found only in Africa and South America, are among the most frightening of all illnesses. Ebola and Marburg, limited to Africa, are the only members of a family known as filoviruses, and they are as bad as these diseases get. The viruses sabotage the body's defenses by invading and eventually killing the white blood cells that are essential to fighting off infections.

Three to 9 days after exposure, the illness comes on suddenly, with a fever and a pounding headache, and swiftly progresses to vomiting and diarrhea. The virus also attacks vital organs like the liver, spleen and pancreas, and ultimately spreads just about everywhere in the body. About half the patients bleed under the skin and from the mouth, nose, intestines and other openings.

There is no vaccine or treatment, and victims can be dead in a week, usually from shock and plummeting blood pressure caused by fluid leaking out of blood vessels. Death rates have been 80 percent to 90 percent for Ebola, and 30 percent to 90 percent for Marburg.

People can catch the virus from animals - primates and possibly bats - and the disease can spread easily from person to person in those who come into contact with bodily fluids from patients. But little is known about the cause of human outbreaks or the animal reservoirs where the virus must live between them.

The international experts who have rushed to Angola have been so busy trying to contain the epidemic that they have had no time to trace its origins. Ultimately, though, finding the source of the disease may help health authorities to prevent future outbreaks.

"We can do that once the situation here is better under control," said Dr. Thomas Grein of the World Health Organization. One possibility is that the disease came from monkeys, which are hunted and eaten in Africa. The animals can harbor the Marburg virus, though they get sick and die from it just as people do. People who eat cooked monkey meat are not necessarily at risk, since heat destroys the virus. But those who hunt and butcher the animals and handle the raw meat run a high risk of infection if the animal was sick.

|

What remains puzzling, though, is why so many children have been infected. Early in the epidemic, scores of babies and children younger than 5 died, and they accounted for a majority of the cases. Now, children make up 30 to 40 percent of the cases, still an unusually high percentage.

The Marburg virus does not spread through the air, and people do not start transmitting it until they are sick; even then, direct contact with bodily fluids is required.

Some researchers suspect that what spread the disease so quickly was contaminated medical equipment, like needles, syringes or intravenous lines. If that occurred, where it occurred is anyone's guess.

Somehow, somewhere, "I think they were getting IV Marburg," said Dr. Pierre Formenty, a virologist with the W.H.O.

Some health officials have blamed the provincial hospital. But Dr. Enzo Pisani, who has worked in Angola for seven years for an Italian charity, Doctors With Africa, insisted that only disposable needles were used there and discarded, never reused. Dr. Pisani said the many small for-profit clinics that dot Uíge, run by people with little or no medical training, were more likely to blame.

He said the neighborhood clinics, which are completely unregulated, were often the first stop for parents with sick children, and provided shots and various intravenous treatments for malaria and other fevers. To save money, he said, they may have reused needles.

In recent days, health experts visiting the houses of infected people found that they were being treated at home with shots and intravenous medicines. This could help spread the disease within households, Mr. Daigle said.

In past Ebola outbreaks in other African nations, hospitals and clinics sometimes acted like distribution centers for the virus: in some, patients were admitted for malaria and then caught Ebola and died.

"Every time you have a hospital, you have amplification," said Dr. Rollin.

Hospitals in Africa are crowded, another ideal condition for spreading infections. Most do not provide meals or much attention from nurses, and family members must feed and care for the patient. Often, the entire family stays at the hospital.

|

The province was ill equipped to deal with the spread of the disease, as it is to fight more common diseases, like malaria, dysentery and yellow fever, that are endemic here.

Sickness and death are so common in children here that doctors say the illness caused by the Marburg virus, which starts with fever and headache like many other tropical diseases, might at first have simply been mistaken for something else.

"Here, every day, if three children die and not four, you are very, very happy," Dr. Pisani said.

Nor is it easy for Uíge to receive international aid. The province is 190 miles northeast of the capital, Luanda, a 12-hour drive along an unpaved road through a region so heavily planted with land mines during 27 years of civil war that travelers are told never to drive off the road, not even onto the shoulder to pass another vehicle.

Only buildings with their own generators have electricity - and even then, only when there is fuel and the machines are working. Cellphones abound, but there is no running water. Windows have no screens.

If this outbreak is stopped, scientists will still be left with a major question: where does the virus lurk between outbreaks?

It must have a natural host in some animal, but one that is not known for Marburg or Ebola. The host would have to be a species that is not wiped out by the virus. That requirement would rule out monkeys and apes, because when they catch Marburg or Ebola, they have even higher death rates than people do. Health authorities in Africa warn people to stay far away from the corpses of dead primates, because they may have died of Ebola.

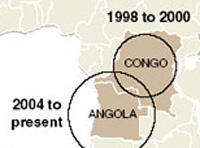

Several Marburg victims in South Africa and Kenya had visited caves before taking ill. And in the outbreak that killed 128 people in Congo from 1998 to 2000, most victims were miners. The link to caves and mines has led scientists to suspect that bats carry the virus. Two victims in the 1980's had visited Kitum Cave in Mount Elgon National Park in Kenya. The cave is full of bats and guano.

Dr. Daniel Bausch, an expert in hemorrhagic fevers at Tulane University who studied the Congo outbreak, said that the mine in Congo, in a region called Durba, was full of bats of many species. Laboratory studies by another researcher, in South Africa, found that bats could carry the virus for long periods without getting sick.

Miners could easily come in contact with virus-laden droppings by touching floors or walls in the mine, and then touch their eyes or mouths and infect themselves, Dr. Bausch said. Primates could also become infected by sleeping in mines or caves.

Researchers captured and tested about 500 bats from the mine and never found the Marburg virus, Dr. Rollin said. But, he added, there were literally millions of bats in the mine, and entire species probably went untested. Sometimes, only one species is the principal carrier of a particular virus. The scientists may simply have tested the wrong species.

Although the reservoir of the Marburg virus has not been found, another aspect of the Congo outbreak points to bats, or to some other creature that inhabits mines and caves: the epidemic stopped when the mine became flooded and people could no longer enter it. But no caves or mines have been implicated in Uíge; the source of Marburg here remains a mystery.

Not much research money was spent on Marburg or Ebola until recent years, when fears of bioterrorism grew and it became apparent that the viruses could be used for germ warfare.

Now, drugs and vaccines are being developed against both viruses. Dr. Heinz Feldmann, a Canadian researcher who set up a lab to test for the virus in Uíge, said his research team had created a vaccine that protected primates against the Marburg virus, but had not yet published the results. The vaccine would probably not be given routinely, but to people at risk during an outbreak.

"We will most likely have some options in a couple of years," Dr. Feldmann said. Whether "they're ever going to be used in these poor people here in Central Africa is a different issue."