|

THE LAND OF THE LIVING AND THE

LAND OF THE DEAD

The History of Man is the record of a hungry creature in search

of food.

Wherever food was plentiful and easily gathered, thither man

travelled to make his home.

The fame of the Nile valley must have spread at an early date.

From far and wide, wild people flocked to the banks of the river.

Surrounded on all sides by desert or sea, it was not easy to reach

these fertile fields and only the hardiest men and women survived.

We do not know who they were. Some came from the interior of

Africa and had woolly hair and thick lips.

Others, with a yellowish skin, came from the desert of Arabia and

the broad rivers of western Asia.

They fought each other for the possession of this wonderful land.

They built villages which their neighbors destroyed and they

rebuilt them with the bricks they had taken from other neighbors

whom they in turn had vanquished.

Gradually a new race developed. They called themselves "remi,"

which means simply "the Men." There was a touch of pride in this

name and they used it in the same sense that we refer to America as

"God's own country."

Part of the year, during the annual flood of the Nile, they lived

on small islands within a country which itself was cut off from the

rest of the world by the sea and the desert. No wonder that these

people were what we call "insular," and had the habits of villagers

who rarely come in contact with their neighbors.

They liked their own ways best. They thought their own habits and

customs just a trifle better than those of anybody else. In the same

way, their own gods were considered more powerful than the gods of

other nations. They did not exactly despise foreigners, but they

felt a mild pity for them and if possible they kept them outside of

the Egyptian domains, lest their own people be corrupted by "foreign

notions."

They were kind-hearted and rarely did anything that was cruel.

They were patient and in business dealings they were rather

indifferent Life came as an easy gift and they never became stingy

and mean like northern people who have to struggle for mere

existence.

When the sun arose above the blood-red horizon of the distant

desert, they went forth to till their fields. When the last rays of

light had disappeared beyond the mountain ridges, they went to bed.

They worked hard, they plodded and they bore whatever happened

with stolid unconcern and profound patience.

They believed that this life was but a short preface to a new

existence which began the moment Death had entered the house. Until

at last, the life of the future came to be regarded as more

important than the life of the present and the people of Egypt

turned their teeming land into one vast shrine for the worship of

the dead.

And as most of the papyrus-rolls of the ancient valley tell

stories of a religious nature we know with great accuracy just what

gods the Egyptians revered and how they tried to assure all possible

happiness and comfort to those who had entered upon the eternal

sleep. In the beginning each little village had possessed a god of

its own.

Often this god was supposed to reside in a queerly shaped stone

or in the branch of a particularly large tree. It was well to be

good friends with him for he could do great harm and destroy the

harvest and prolong the period of drought until the people and the

cattle had all died of thirst. Therefore the villages made him

presents--offered him things to eat or a bunch of flowers.

When the Egyptians went forth to fight their enemies the god must

needs be taken along, until he became a sort of battle flag around

which the people rallied in time of danger.

But when the country grew older and better roads had been built

and the Egyptians had begun to travel, the old "fetishes," as such

chunks of stone and wood were called, lost their importance and were

thrown away or were left in a neglected corner or were used as

doorsteps or chairs.

Their place was taken by new gods who were more powerful than the

old ones had been and who represented those forces of nature which

influenced the lives of the Egyptians of the entire valley.

First among these was the Sun which makes all things grow.

Next came the river Nile which tempered the heat of the day and

brought rich deposits of clay to refresh the fields and make them

fertile.

Then there was the kindly Moon which at night rowed her little

boat across the arch of heaven and there was Thunder and there was

Lightning and there were any number of things which could make life

happy or miserable according to their pleasure and desire.

Ancient man, entirely at the mercy of these forces of nature,

could not get rid of them as easily as we do when we plant lightning

rods upon our houses or build reservoirs which keep us alive during

the summer months when there is no rain.

On the contrary they formed an intimate part of his daily

life--they accompanied him from the moment he was put into his

cradle until the day that his body was prepared for eternal rest.

Neither could he imagine that such vast and powerful phenomena as

a bolt of lightning or the flood of a river were mere impersonal

things. Some one--somewhere--must be their master and must direct

them as the engineer directs his engine or a captain steers his

ship.

A God-in-Chief was therefore created, like the commanding general

of an army.

A number of lower officers were placed at his disposal.

Within their own territory each one could act independently.

In grave matters, however, which affected the happiness of all

the people, they must take orders from their master.

The Supreme Divine Ruler of the land of Egypt was called Osiris,

and all the little Egyptian children knew the story of his wonderful

life.

Once upon a time, in the valley of the Nile, there lived a king

called Osiris.

He was a good man who taught his subjects how to till their

fields and who gave his country just laws. But he had a bad brother

whose name was Seth.

Now Seth envied Osiris because he was so virtuous and one day he

invited him to dinner and afterwards he said that he would like to

show him something. Curious Osiris asked what it was and Seth said

that it was a funnily shaped coffin which fitted one like a suit of

clothes. Osiris said that he would like to try it. So he lay down in

the coffin but no sooner was he inside when bang!--Seth shut the

lid. Then he called for his servants and ordered them to throw the

coffin into the Nile.

Soon the news of his terrible deed spread throughout the land.

Isis, the wife of Osiris, who had loved her husband very dearly,

went at once to the banks of the Nile, and after a short while the

waves threw the coffin upon the shore. Then she went forth to tell

her son Horus, who ruled in another land, but no sooner had she left

than Seth, the wicked brother, broke into the palace and cut the

body of Osiris into fourteen pieces.

When Isis returned, she discovered what Seth had done. She took

the fourteen pieces of the dead body and sewed them together and

then Osiris came back to life and reigned for ever and ever as king

of the lower world to which the souls of men must travel after they

have left the body.

As for Seth, the Evil One, he tried to escape, but Horus, the son

of Osiris and Isis, who had been warned by his mother, caught him

and slew him.

This story of a faithful wife and a wicked brother and a dutiful

son who avenged his father and the final victory of virtue over

wickedness formed the basis of the religious life of the people of

Egypt.

Osiris was regarded as the god of all living things which

seemingly die in the winter and yet return to renewed existence the

next spring. As ruler of the Life Hereafter, he was the final judge

of the acts of men, and woe unto him who had been cruel and unjust

and had oppressed the weak.

As for the world of the departed souls, it was situated beyond

the high mountains of the west (which was also the home of the young

Nile) and when an Egyptian wanted to say that someone had died, he

said that he "had gone west."

Isis shared the honors and the duties of Osiris with him. Their

son Horus, who was worshipped as the god of the Sun (hence the word

"horizon," the place where the sun sets) became the first of a new

line of Egyptian kings and all the Pharaohs of Egypt had Horus as

their middle name.

Of course, each little city and every small village continued to

worship a few divinities of their own. But generally speaking, all

the people recognized the sublime power of Osiris and tried to gain

his favor.

This was no easy task, and led to many strange customs. In the

first place, the Egyptians came to believe that no soul could enter

into the realm of Osiris without the possession of the body which

had been its place of residence in this world.

Whatever happened, the body must be preserved after death, and it

must be given a permanent and suitable home. Therefore as soon as a

man had died, his corpse was embalmed. This was a difficult and

complicated operation which was performed by an official who was

half doctor and half priest, with the help of an assistant whose

duty it was to make the incision through which the chest could be

filled with cedar-tree pitch and myrrh and cassia. This assistant

belonged to a special class of people who were counted among the

most despised of men. The Egyptians thought it a terrible thing to

commit acts of violence upon a human being, whether dead or living,

and only the lowest of the low could be hired to perform this

unpopular task.

Afterwards the priest took the body again and for a period of ten

weeks he allowed it to be soaked in a solution of natron which was

brought for this purpose from the distant desert of Libya. Then the

body had become a "mummy" because it was filled with "Mumiai" or

pitch. It was wrapped in yards and yards of specially prepared linen

and it was placed in a beautifully decorated wooden coffin, ready to

be removed to its final home in the western desert.

The grave itself was a little stone room in the sand of the

desert or a cave in a hill-side.

After the coffin had been placed in the center the little room

was well supplied with cooking utensils and weapons and statues (of

clay or wood) representing bakers and butchers who were expected to

wait upon their dead master in case he needed anything. Flutes and

fiddles were added to give the occupant of the grave a chance to

while away the long hours which he must spend in this "house of

eternity."

Then the roof was covered with sand and the dead Egyptian was

left to the peaceful rest of eternal sleep.

But the desert is full of wild creatures, hyenas and wolves, and

they dug their way through the wooden roof and the sand and ate up

the mummy.

This was a terrible thing, for then the soul was doomed to wander

forever and suffer agonies of a man without a home. To assure the

corpse all possible safety a low wall of brick was built around the

grave and the open space was filled with sand and gravel. In this

way a low artificial hill was made which protected the mummy against

wild animals and robbers.

Then one day, an Egyptian who had just buried his Mother, of whom

he had been particularly fond, decided to give her a monument that

should surpass anything that had ever been built in the valley of

the Nile.

He gathered his serfs and made them build an artificial mountain

that could be seen for miles around. The sides of this hill he

covered with a layer of bricks that the sand might not be blown

away.

People liked the novelty of the idea.

Soon they were trying to outdo each other and the graves rose

twenty and thirty and forty feet above the ground.

At last a rich nobleman ordered a burial chamber made of solid

stone.

On top of the actual grave where the mummy rested, he constructed

a pile of bricks which rose several hundred feet into the air. A

small passage-way gave entrance to the vault and when this passage

was closed with a heavy slab of granite the mummy was safe from all

intrusion.

The King of course could not allow one of his subjects to outdo

him in such a matter. He was the most powerful man of all Egypt who

lived in the biggest house and therefore he was entitled to the best

grave.

What others had done in brick he could do with the help of more

costly materials.

Pharaoh sent his officers far and wide to gather workmen. He

constructed roads. He built barracks in which the workmen could live

and sleep (you may see those barracks this very day). Then he set to

work and made himself a grave which was to endure for all time.

We call this great pile of masonry a "pyramid."

The origin of the word is a curious one.

When the Greeks visited Egypt the Pyramids were already several

thousand years old.

Of course the Egyptians took their guests into the desert to see

these wondrous sights just as we take foreigners to gaze at the

Wool-worth Tower and Brooklyn Bridge.

The Greek guest, lost in admiration, waved his hands and asked

what the strange mountains might be.

His guide thought that he referred to the extraordinary height

and said "Yes, they are very high indeed."

The Egyptian word for height was "pir-em-us."

The Greek must have thought that this was the name of the whole

structure and giving it a Greek ending he called it a "pyramis."

We have changed the "s" into a "d" but we still use the same

Egyptian word when we talk of the stone graves along the banks of

the Nile.

The biggest of these many pyramids, which was built fifty

centuries ago, was five hundred feet high.

At the base it was seven hundred and fifty-five feet wide.

It covered more than thirteen acres of desert, which is three

times as much space as that occupied by the church of Saint Peter,

the largest edifice of the Christian world.

During twenty years, over a hundred thousand men were used to

carry the stones from the distant peninsula of Sinai--to ferry them

across the Nile (how they ever managed to do this we do not

understand)--to drag them halfway across the desert and finally

hoist them into their correct position.

But so well did Pharaoh's architects and engineers perform their

task that the narrow passage-way which leads to the royal tomb in

the heart of the pyramid has never yet been pushed out of shape by

the terrific weight of those thousands and thousands of tons of

stone which press upon it from all sides.

THE

MAKING OF A STATE

Nowadays we all are members of a "state."

We may be Frenchmen or Chinamen or Russians; we may live in the

furthest corner of Indonesia (do you know where that is?), but in

some way or other we belong to that curious combination of people

which is called the "state."

It does not matter whether we recognize a king or an emperor or a

president as our ruler. We are born and we die as a small part of

this large Whole and no one can escape this fate.

The "state," as a matter of fact, is quite a recent invention.

The earliest inhabitants of the world did not know what it was.

Every family lived and hunted and worked and died for and by

itself. Sometimes it happened that a few of these families, for the

sake of greater protection against the wild animals and against

other wild people, formed a loose alliance which was called a tribe

or a clan. But as soon as the danger was past, these groups of

people acted again by and for themselves and if the weak could not

defend their own cave, they were left to the mercies of the hyena

and the tiger and nobody was very sorry if they were killed.

In short, each person was a nation unto himself and he felt no

responsibility for the happiness and safety of his neighbor. Very,

very slowly this was changed and Egypt was the first country where

the people were organized into a well-regulated empire.

The Nile was directly responsible for this useful development. I

have told you how in the summer of each year the greater part of the

Nile valley and the Nile delta is turned into a vast inland sea. To

derive the greatest benefit from this water and yet survive the

flood, it had been necessary at certain points to build dykes and

small islands which would offer shelter for man and beast during the

months of August and September. The construction of these little

artificial islands however had not been simple.

A single man or a single family or even a small tribe could not

construct a river-dam without the help of others.

However much a farmer might dislike his neighbors he disliked

getting drowned even more and he was obliged to call upon the entire

country-side when the water of the river began to rise and

threatened him and his wife and his children and his cattle with

destruction.

Necessity forced the people to forget their small differences and

soon the entire valley of the Nile was covered with little

combinations of people who constantly worked together for a common

purpose and who depended upon each other for life and prosperity.

Out of such small beginnings grew the first powerful State.

It was a great step forward along the road of progress.

It made the land of Egypt a truly inhabitable place. It meant the

end of lawless murder. It assured the people greater safety than

ever before and gave the weaker members of the tribe a chance to

survive. Nowadays, when conditions of absolute disorder exist only

in the jungles of Africa, it is hard to imagine a world without laws

and policemen and judges and health officers and hospitals and

schools.

But five thousand years ago, Egypt stood alone as an organized

state and was greatly envied by those of her neighbors who were

obliged to face the difficulties of life single-handedly.

A state, however, is not only composed of citizens.

There must be a few men who execute the laws and who, in case of

an emergency, take command of the entire community. Therefore no

country has ever been able to endure without a single head, be he

called a King or an Emperor or a Shah (as in Persia) or a President,

as he is called in our own land.

In ancient Egypt, every village recognized the authority of the

Village-Elders, who were old men and possessed greater experience

than the young ones. These Elders selected a strong man to command

their soldiers in case of war and to tell them what to do when there

was a flood. They gave him a title which distinguished him from the

others. They called him a King or a prince and obeyed his orders for

their own common benefit.

Therefore in the oldest days of Egyptian history, we find the

following division among the people:

The majority are peasants.

All of them are equally rich and equally poor.

They are ruled by a powerful man who is the commander-in-chief of

their armies and who appoints their judges and causes roads to be

built for the common benefit and comfort.

He also is the chief of the police force and catches the thieves.

In return for these valuable services he receives a certain

amount of everybody's money which is called a tax. The greater part

of these taxes, however, do not belong to the King personally. They

are money entrusted to him to be used for the common good.

But after a short while a new class of people, neither peasants

nor king, begins to develop. This new class, commonly called the

nobles, stands between the ruler and his subjects.

Since those early days it has made its appearance in the history

of every country and it has played a great role in the development

of every nation.

I must try and explain to you how this class of nobles developed

out of the most commonplace circumstances of everyday life and why

it has maintained itself to this very day, against every form of

opposition.

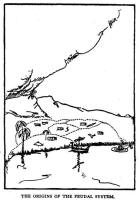

To make my story quite clear, I have drawn a picture.

It shows you five Egyptian farms. The original owners of these

farms had moved into Egypt years and years ago. Each had taken a

piece of unoccupied land and had settled down upon it to raise grain

and cows and pigs and do whatever was necessary to keep themselves

and their children alive. Apparently they had the same chance in

life.

How then did it happen that one became the ruler of his neighbors

and got hold of all their fields and barns without breaking a single

law?

One day after the harvest, Mr. Fish (you see his name in

hieroglyphics on the map) sent his boat loaded with grain to the

town of Memphis to sell the cargo to the inhabitants of central

Egypt. It happened to have been a good year for the farmer and Fish

got a great deal of money for his wheat. After ten days the boat

returned to the homestead and the captain handed the money which he

had received to his employer.

A few weeks later, Mr. Sparrow, whose farm was next to that of

Fish, sent his wheat to the nearest market. Poor Sparrow had not

been very lucky for the last few years. But he hoped to make up for

his recent losses by a profitable sale of his grain. Therefore he

had waited until the price of wheat in Memphis should have gone a

little higher.

That morning a rumor had reached the village of a famine in the

island of Crete. As a result the grain in the Egyptian markets had

greatly increased in value.

Sparrow hoped to profit through this unexpected turn of the

market and he bade his skipper to hurry.

The skipper handled the rudder of his craft so clumsily that the

boat struck a rock and sank, drowning the mate who was caught under

the sail.

Sparrow not only lost all his grain and his ship but he was also

forced to pay the widow of his drowned mate ten pieces of gold to

make up for the loss of her husband.

These disasters occurred at the very moment when Sparrow could

not afford another loss.

Winter was near and he had no money to buy cloaks for his

children. He had put off buying new hoes and spades for such a long

time that the old ones were completely worn out. He had no seeds for

his fields. He was in a desperate plight.

He did not like his neighbor, Mr. Fish, any too well but there

was no way out. He must go and humbly he must ask for the loan of a

small sum of money.

He called on Fish. The latter said that he would gladly let him

have whatever he needed but could Sparrow put up any sort of

guaranty?

Sparrow said, "Yes." He would offer his own farm as a pledge of

good faith.

Unfortunately Fish knew all about that farm. It had belonged to

the Sparrow family for many generations. But the Father of the

present owner had allowed himself to be terribly cheated by a

Phoenician trader who had sold him a couple of "Phrygian Oxen"

(nobody knew what the name meant) which were said to be of a very

fine breed, which needed little food and performed twice as much

labor as the common Egyptian oxen. The old farmer had believed the

solemn words of the impostor. He had bought the wonderful beasts,

greatly envied by all his neighbors.

They had not proved a success.

They were very stupid and very slow and exceedingly lazy and

within three weeks they had died from a mysterious disease.

The old farmer was so angry that he suffered a stroke and the

management of his estate was left to the son, who worked hard but

without much result.

The loss of his grain and his vessel were the last straw.

Young Sparrow must either starve or ask his neighbor to help him

with a loan.

Fish who was familiar with the lives of all his neighbors (he was

that kind of person, not because he loved gossip but one never knew

how such information might come in handy) and who knew to a penny

the state of affairs in the Sparrow household, felt strong enough to

insist upon certain terms. Sparrow could have all the money he

needed upon the following condition. He must promise to work for

Fish six weeks of every year and he must allow him free access to

his grounds at all times.

Sparrow did not like these terms, but the days were growing

shorter and winter was coming on fast and his family were without

food.

He was forced to accept and from that time on, he and his sons

and daughters were no longer quite as free as they had been before.

They did not exactly become the servants or the slaves of their

neighbor, but they were dependent upon his kindness for their own

livelihood. When they met Fish in the road they stepped aside and

said "Good morning, sir." And he answered them--or not--as the case

might be.

He now owned a great deal of water-front, twice as much as

before.

He had more land and more laborers and he could raise more grain

than in the past years. The nearby villagers talked of the new house

he was building and in a general way, he was regarded as a man of

growing wealth and importance.

Late that summer an unheard-of-thing happened.

It rained.

The oldest inhabitants could not remember such a thing, but it

rained hard and steadily for two whole days. A little brook, the

existence of which everybody had forgotten, was suddenly turned into

a wild torrent. In the middle of the night it came thundering down

from the mountains and destroyed the harvest of the farmer who

occupied the rocky ground at the foot of the hills. His name was Cup

and he too had inherited his land from a hundred other Cups who had

gone before. The damage was almost irreparable. Cup needed new seed

grain and he needed it at once. He had heard Sparrow's story. He too

hated to ask a favor of Fish who was known far and wide as a shrewd

dealer. But in the end, he found his way to the Fishs' homestead and

humbly begged for the loan of a few bushels of wheat. He got them

but not until he had agreed to work two whole months of each year on

the farm of Fish.

Fish was now doing very well. His new house was ready and he

thought the time had come to establish himself as the head of a

household.

Just across the way, there lived a farmer who had a young

daughter. The name of this farmer was Knife. He was a happy-go-lucky

person and he could not give his child a large dowry.

Fish called on Knife and told him that he did not care for money.

He was rich and he was willing to take the daughter without a single

penny. Knife, however, must promise to leave his land to his

son-in-law in case he died.

This was done.

The will was duly drawn up before a notary, the wedding took

place and Fish now possessed (or was about to possess) the greater

part of four farms.

It is true there was a fifth farm situated right in between the

others. But its owner, by the name of Sickle, could not carry his

wheat to the market without crossing the lands over which Fish held

sway. Besides, Sickle was not very energetic and he willingly hired

himself out to Fish on condition that he and his old wife be given a

room and food and clothes for the rest of their days. They had no

children and this settlement assured them a peaceful old age. When

Sickle died, a distant nephew appeared who claimed a right to his

uncle's farm. Fish had the dogs turned loose on him and the fellow

was never seen again.

These transactions had covered a period of twenty years.

The younger generations of the Cup and

Sickle and Sparrow families accepted their situation in life

without questioning. They knew old Fish as "the Squire" upon whose

good-will they were more or less dependent if they wanted to succeed

in life.

When the old man died he left his son many wide acres and a

position of great influence among his immediate neighbors.

Young Fish resembled his father. He was very able and had a great

deal of ambition. When the king of Upper Egypt went to war against

the wild Berber tribes, he volunteered his services.

He fought so bravely that the king appointed him Collector of the

Royal Revenue for three hundred villages.

Often it happened that certain farmers could not pay their tax.

Then young Fish offered to give them a small loan.

Before they knew it, they were working for the Royal Tax

Gatherer, to repay both the money which they had borrowed and the

interest on the loan.

The years went by and the Fish family reigned supreme in the land

of their birth. The old home was no longer good enough for such

important people.

A noble hall was built (after the pattern of the Royal Banqueting

Hall of Thebes). A high wall was erected to keep the crowd at a

respectful distance and Fish never went out without a bodyguard of

armed soldiers.

Twice a year he travelled to Thebes to be with his King, who

lived in the largest palace of all Egypt and who was therefore known

as "Pharaoh," the owner of the "Big House."

Upon one of his visits, he took Fish the Third, grandson of the

founder of the family, who was a handsome young fellow.

The daughter of Pharaoh saw the youth and desired him for her

husband. The wedding cost Fish most of his fortune, but he was still

Collector of the Royal Revenue and by treating the people without

mercy he was able to fill his strong-box in less than three years.

When he died he was buried in a small Pyramid, just as if he had

been a member of the Royal Family, and a daughter of Pharaoh wept

over his grave.

That is my story which begins somewhere along the banks of the

Nile and which in the course of three generations lifts a farmer

from the ranks of his own humble ancestors and drops him outside the

gate but near the throne-room of the King's palace.

What happened to Fish, happened to a large number of equally

energetic and resourceful men.

They formed a class apart.

They married each other's daughters and in this way they kept the

family fortunes in the hands of a small number of people.

They served the King faithfully as officers in his army and as

collectors of his taxes.

They looked after the safety of the roads and the waterways.

They performed many useful tasks and among themselves they obeyed

the laws of a very strict code of honor.

If the Kings were bad, the nobles were apt to be bad too.

When the Kings were weak the nobles often managed to get hold of

the State.

Then it often happened that the people arose in their wrath and

destroyed those who oppressed them.

Many of the old nobles were killed and a new division of the land

took place which gave everybody an equal chance.

But after a short while the old story repeated itself.

This time it was perhaps a member of the Sparrow family who used

his greater shrewdness and industry to make himself master of the

countryside while the descendants of Fish (of glorious memory!) were

reduced to poverty.

Otherwise very little was changed.

The faithful peasants continued to work and pay taxes.

The equally faithful tax gatherers continued to gather wealth.

But the old Nile, indifferent to the ambitions of men, flowed as

placidly as ever between its age-worn banks and bestowed its fertile

blessings upon the poor and upon the rich with the impartial justice

which is found only in the forces of nature. |