|

THE RISE AND FALL OF EGYPT

We often hear it said that "civilization travels westward." What

we mean is that hardy pioneers have crossed the Atlantic Ocean and

settled along the shores of New England and New Netherland--that

their children have crossed the vast prairies--that their

great-grandchildren have moved into California--and that the present

generation hopes to turn the vast Pacific into the most important

sea of the ages.

As a matter of fact, "civilization" never remains long in the

same spot. It is always going somewhere but it does not always move

westward by any means. Sometimes its course points towards the east

or the south. Often it zigzags across the map. But it keeps moving.

After two or three hundred years, civilization seems to say, "Well,

I have been keeping company with these particular people long

enough," and it packs its books and its science and its art and its

music, and wanders forth in search of new domains. But no one knows

whither it is bound, and that is what makes life so interesting.

In the case of Egypt, the center of civilization moved northward

and southward, along the banks of the Nile. First of all, as I told

you, people from all over Africa and western Asia moved into the

valley and settled down. Thereupon they formed small villages and

townships and accepted the rule of a Commander-in-Chief, who was

called Pharaoh, and who had his capital in Memphis, in the lower

part of Egypt.

After a couple of thousand years, the rulers of this ancient

house became too weak to maintain themselves. A new family from the

town of Thebes, 350 miles towards the south in Upper Egypt, tried to

make itself master of the entire valley. In the year 2400 B.C. they

succeeded. As rulers of both Upper and Lower Egypt, they set forth

to conquer the rest of the world. They marched towards the sources

of the Nile (which they never reached) and conquered black Ethiopia.

Next they crossed the desert of Sinai and invaded Syria where they

made their name feared by the Babylonians and Assyrians. The

possession of these outlying districts assured the safety of Egypt

and they could set to work to turn the valley into a happy home, for

as many of the people as could find room there. They built many new

dikes and dams and a vast reservoir in the desert which they filled

with water from the Nile to be kept and used in case of a prolonged

drought. They encouraged people to devote themselves to the study of

mathematics and astronomy so that they might determine the time when

the floods of the Nile were to be expected. Since for this purpose

it was necessary to have a handy method by which time could be

measured, they established the year of 365 days, which they divided

into twelve months.

Contrary to the old tradition which made the Egyptians keep away

from all things foreign, they allowed the exchange of Egyptian

merchandise for goods which had been carried to their harbors from

elsewhere.

They traded with the Greeks of Crete and with the Arabs of

western Asia and they got spices from the Indies and they imported

gold and silk from China.

But all human institutions are subject to certain definite laws

of progress and decline and a State or a dynasty is no exception.

After four hundred years of prosperity, these mighty kings showed

signs of growing tired. Rather than ride a camel at the head of

their army, the rulers of the great Egyptian Empire stayed within

the gates of their palace and listened to the music of the harp or

the flute.

One day there came rumors to the town of Thebes that wild tribes

of horsemen had been pillaging along the frontiers. An army was sent

to drive them away. This army moved into the desert. To the last man

it was killed by the fierce Arabs, who now marched towards the Nile,

bringing their flocks of sheep and their household goods.

Another army was told to stop their progress. The battle was

disastrous for the Egyptians and the valley of the Nile was open to

the invaders.

They rode fleet horses and they used bows and arrows. Within a

short time they had made themselves master of the entire country.

For five centuries they ruled the land of Egypt. They removed the

old capital to the Delta of the Nile.

They oppressed the Egyptian peasants.

They treated the men cruelly and they killed the children and

they were rude to the ancient gods. They did not like to live in the

cities but stayed with their flocks in the open fields and therefore

they were called the Hyksos, which means the Shepherd Kings.

At last their rule grew unbearable.

A noble family from the city of Thebes placed itself at the head

of a national revolution against the foreign usurpers. It was a

desperate fight but the Egyptians won. The Hyksos were driven out of

the country, and they went back to the desert whence they had come.

The experience had been a warning to the Egyptian people. Their five

hundred years of foreign slavery had been a terrible experience.

Such a thing must never happen again. The frontier of the fatherland

must be made so strong that no one dare to attack the holy soil.

A new Theban king, called Tethmosis, invaded Asia and never

stopped until he reached the plains of Mesopotamia. He watered his

oxen in the river Euphrates, and Babylon and Nineveh trembled at the

mention of his name. Wherever he went, he built strong fortresses,

which were connected by excellent roads. Tethmosis, having built a

barrier against future invasions, went home and died. But his

daughter, Hatshepsut, continued his good work. She rebuilt the

temples which the Hyksos had destroyed and she founded a strong

state in which soldiers and merchants worked together for a common

purpose and which was called the New Empire, and lasted from 1600 to

1300 B.C.

Military nations, however, never last very long. The larger the

empire, the more men are needed for its defense and the more men

there are in the army, the fewer can stay at home to work the farms

and attend to the demands of trade. Within a few years, the Egyptian

state had become top-heavy and the army, which was meant to be a

bulwark against foreign invasion, dragged the country into ruin from

sheer lack of both men and money.

Without interruption, wild people from Asia were attacking those

strong walls behind which Egypt was hoarding the riches of the

entire civilized world.

At first the Egyptian garrisons could hold their own.

One day, however, in distant Mesopotamia, there arose a new

military empire which was called Assyria. It cared for neither art

nor science, but it could fight. The Assyrians marched against the

Egyptians and defeated them in battle. For more than twenty years

they ruled the land of the Nile. To Egypt this meant the beginning

of the end.

A few times, for short periods, the people managed to regain

their independence. But they were an old race, and they were worn

out by centuries of hard work.

The time had come for them to disappear from the stage of history

and surrender their leadership as the most civilized people of the

world. Greek merchants were swarming down upon the cities at the

mouth of the Nile.

A new capital was built at Sais, near the mouth of the Nile, and

Egypt became a purely commercial state, the half-way house for the

trade between western Asia and eastern Europe.

After the Greeks came the Persians, who conquered all of northern

Africa.

Two centuries later, Alexander the Great turned the ancient land

of the Pharaoh? into a Greek province. When he died, one of his

generals, Ptolemy by name, established himself as the independent

king of a new Egyptian state.

The Ptolemy family continued to rule for two hundred years.

In the year 30 B.C., Cleopatra, the last of the Ptolemys, killed

herself, rather than become a prisoner of the victorious Roman

general, Octavianus.

That was the end.

Egypt became part of the Roman Empire and her life as an

independent state ceased for all time.

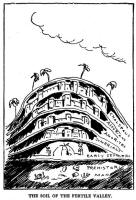

MESOPOTAMIA, THE COUNTRY

BETWEEN THE RIVERS

I am going to take you to the top of the highest pyramid.

It is a good deal of a climb.

The casing of fine stones which in the beginning covered the

rough granite blocks which were used to construct this artificial

mountain, has long since worn off or has been stolen to help build

new Roman cities. A goat would have a fine time scaling this strange

peak. But with the help of a few Arab boys, we can get to the top

after a few hours of hard work, and there we can rest and look far

into the next chapter of the history of the human race.

Way, way off, in the distance, far beyond the yellow sands of the

vast desert, through which the old Nile had cut herself a way to the

sea, you will (if you have the eyes of a hawk), see something

shimmering and green.

It is a valley situated between two big rivers.

It is the most interesting spot of the ancient map.

It is the Paradise of the Old Testament.

It is the old land of mystery and wonder which the Greeks called

Mesopotamia.

The word "Mesos" means "middle" or "in between" and "potomos" is

the Greek expression for river. (Just think of the Hippopotamus, the

horse or "hippos" that lives in the rivers.) Mesopotamia, therefore,

meant a stretch of land "between the rivers." The two rivers in this

case were the Euphrates which the Babylonians called the "Purattu"

and the Tigris, which the Babylonians called the "Diklat." You will

see them both upon the map. They begin their course amidst the snows

of the northern mountains of Armenia and slowly they flow through

the southern plain until they reach the muddy banks of the Persian

Gulf. But before they have lost themselves amidst the waves of this

branch of the Indian Ocean, they have performed a great and useful

task.

They have turned an otherwise arid and dry region into the only

fertile spot of western Asia.

That fact will explain to you why Mesopotamia was so very popular

with the inhabitants of the northern mountains and the southern

desert.

It is a well-known fact that all living beings like to be

comfortable. When it rains, the cat hastens to a place of shelter.

When it is cold, the dog finds a spot in front of the stove. When

a certain part of the sea becomes more salty than it has been before

(or less, for that matter) myriads of little fishes swim hastily to

another part of the wide ocean. As for the birds, a great many of

them move from one place to another regularly once a year. When the

cold weather sets in, the geese depart, and when the first swallow

returns, we know that summer is about to smile upon us.

Man is no exception to this rule. He likes the warm stove much

better than the cold wind. Whenever he has the choice between a good

dinner and a crust of bread, he prefers the dinner. He will live in

the desert or in the snow of the arctic zone if it is absolutely

necessary. But offer him a more agreeable place of residence and he

will accept without a moment's hesitation. This desire to improve

his condition, which really means a desire to make life more

comfortable and less wearisome, has been a very good thing for the

progress of the world.

It has driven the white people of Europe to the ends of the

earth.

It has populated the mountains and the plains of our own country.

It has made many millions of men travel ceaselessly from east to

west and from south to north until they have found the climate and

the living conditions which suit them best.

In the western part of Asia this instinct which compels living

beings to seek the greatest amount of comfort possible with the

smallest expenditure of labor forced both the inhabitants of the

cold and inhospitable mountains and the people of the parched desert

to look for a new dwelling place in the happy valley of Mesopotamia.

It caused them to fight for the sole possession of this Paradise

upon Earth.

It forced them to exercise their highest power of inventiveness

and their noblest courage to defend their homes and farms and their

wives and children against the newcomers, who century after century

were attracted by the fame of this pleasant spot.

This constant rivalry was the cause of an everlasting struggle

between the old and established tribes and the others who clamored

for their share of the soil.

Those who were weak and those who did not have a great deal of

energy had little chance of success.

Only the most intelligent and the bravest survived. That will

explain to you why Mesopotamia became the home of a strong race of

men, capable of creating that state of civilization which was to be

of such enormous benefit to all later generations. |